When we refer to sensors which are used to study the responding body, we mean the use of sensors to respond to the body’s internal processes. These can be sensed by using what are called physiological sensors.

Electrical physiological sensors

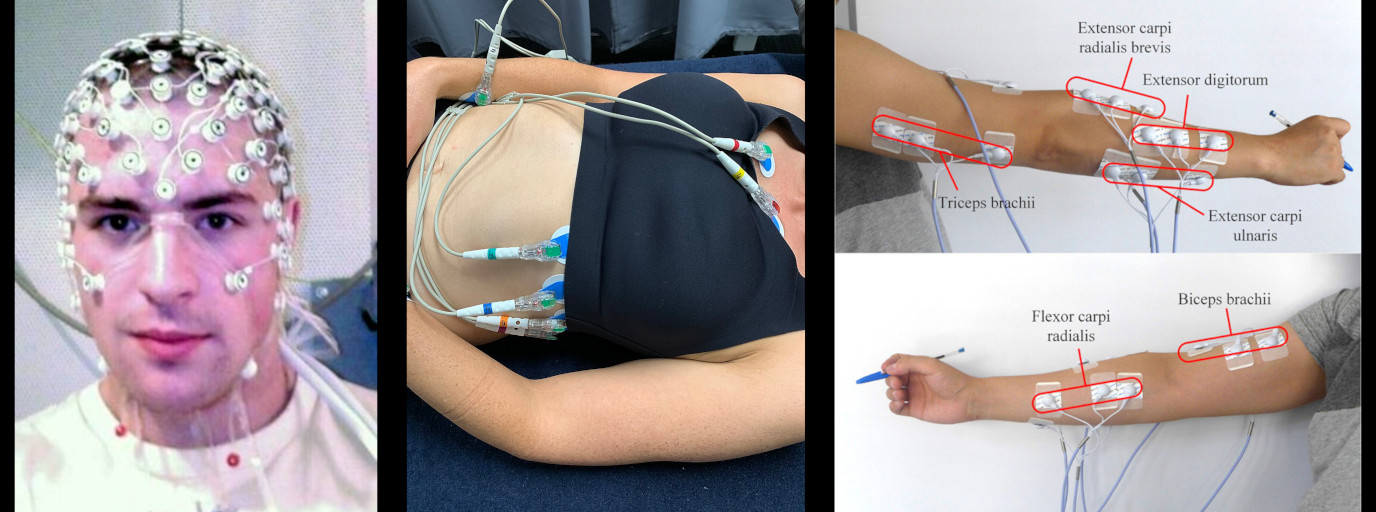

Some common physiological sensors measure electrical signals on the surface of the body - so for example an electrocardiogram (ECG) based heart rate sensor measures electrical voltages between multiple points on the skin, which are affected by the beating of the user’s heart, allowing measurements including heart rate to be taken. Breathing rate can also be inferred from these sensors. Electromyography (EMG) uses similar techniques but with skin electrodes placed either side of a muscle - this allows the sensing of how hard a muscle is being contracted.

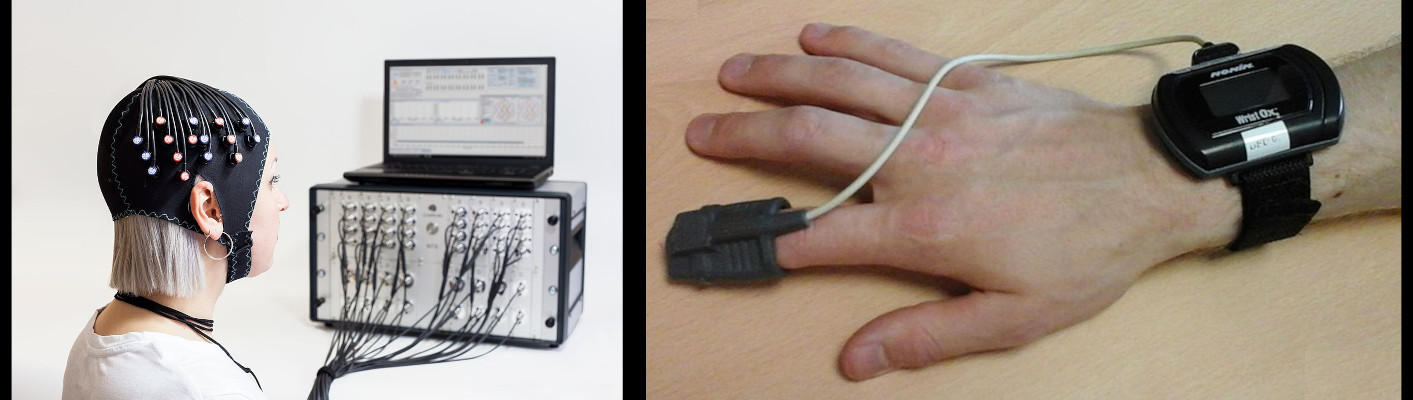

Electro-encephalography (EEG) uses similar techniques to measure voltage differentials across a person’s scalp; this gives a real-time measurement of brain activity across a range of areas of the brain. The signals from EMG and ECG sensors are well understood and relatively easy to interpret; EEG signals are far less clear-cut, requiring significant processing to make useful inferences from them. They can be used for things such as measuring mental effort, controlling things through specific targeted thought processes, and a wide range of brain-computer-interface(BCI) possibilities.

Some physiological processes happen deep within the body - implanted technologies, which embed electrical connections inside the wearer’s body offer potential for understanding these processes. As examples, some brain-computer-interface technologies use electrodes that connect deeper within the brain, to allow understanding of non-surface areas of the brain, and continuous blood glucose monitors embed a sensor inside the wearer’s body to allow real-time monitoring of their blood sugar levels as an aid to managing diabetes. There are also ingestible sensors, small electronic pills which can be swallowed and for as long as they remain in the body can wirelessly transmit information on deep body state to external receivers; these are used for example in studies where accurate body temperature is needed despite the body being in an extreme environment. By swallowing a temperature sensor pill, core body temperature can be monitored accurately even when the external body is subject to temperatures or conditions which would cause traditional body monitoring to fail.

Other wearable physiological sensing

Electrical physiological sensors are very powerful; however in many situations they lack practicality; for example EEG headsets and ECG based heart monitoring often require the application of medical electrode pads and wires, which can both be an invasive process in itself, and can be limited by factors such as thick hair. There are a range of other worn sensors which can be used to detect the body’s physiological signals. These include: breathing sensing using stretch sensors across the user’s chest; photoplethysmography based heart rate sensing, which uses a small LED placed close to the user’s wrist or finger so it shines into the skin, along with photodetectors which detect how much light is shining back, this allows the sensing of blood moving under the skin, which allows estimation of heart rate and blood oxygen levels. Functional-near-infrared-spectroscopy does a similar thing for the brain, using infrared light to allow identification of near-surface brain activity in a less invasive way than electrical sensing methods.

External physiological sensors

Physiological processes can also be sensed using sensors that are not worn by the user. For example work has been done to demonstrate that cameras can be used to measure heart and breathing rates (Procházka et al. 2016), and microphones have been used for breath sensing. There are also more specialised external physiological sensors such as radars which can be used to sense heart and breathing activity - see e.g. Xu et al (2021).

Two sensor-based systems using physiological sensors

The Broncomatic (Marshall et al. 2011) is a sensor driven amusement ride. We made it by repurposing a rodeo bull ride. In Broncomatic, rather than the rotating ride being controlled by an operator or a preset program, the ride instead responds to rider breathing, rotating one way on inhalation and the other way as they exhale. As the ride goes on, this response becomes more forceful. This creates an interesting and fun dynamic where the rider must control their breath to stay on the ride, but the spinning of the ride makes it difficult for them to control their breathing.

The Guts Game (Li et al. 2020) is a game where players eat an ingestible core body temperature sensing pill. During the several hours that the pill remains in their body, they must compete to perform tasks which alter their body temperature in particular ways. For example when told to raise their core body temperature, they could exercise, or drink extremely hot drinks, or go somewhere hot. What is most effective changes depending on how far through the body the sensor pill is. This creates a fun game which focuses players on understanding how their body works, and what affects their core temperature.

References

- Xu, H., Ebrahim, M.P., Hasan, K., Heydari, F., Howley, P. and Yuce, M.R., 2021. Accurate Heart Rate and Respiration Rate Detection Based on a Higher-Order Harmonics Peak Selection Method Using Radar Non-Contact Sensors. Sensors, 22(1), p.83.

- Procházka, A., Schätz, M., Vyšata, O. and Vališ, M., 2016. Microsoft kinect visual and depth sensors for breathing and heart rate analysis. Sensors, 16(7), p.996.

- Li, Z., Wang, Y., Greuter, S. and Mueller, F.F., 2020, April. Ingestible sensors as design material for bodily play. In Extended Abstracts of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1-8).

- Marshall, J., Rowland, D., Rennick Egglestone, S., Benford, S., Walker, B. and McAuley, D., 2011, May. Breath control of amusement rides. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human Factors in computing systems (pp. 73-82).